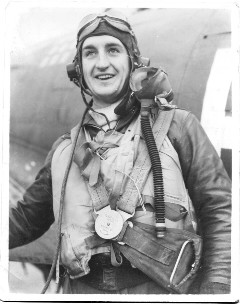

Francis S. Gabreski was the leading

American air ace in Europe in World War II who later in life tangled less

triumphantly with political perils as head of the Long Island Rail Road.,

Flying single-engine P-47 Thunderbolt fighters, Mr. Gabreski downed 28

Messerschmitts and Focke-Wulfs over France and Germany between Aug. 24,

1943, and July 5, 1944, and destroyed three more German aircraft on the

ground.

He was captured in late July 1944 after crash-landing near Koblenz,

Germany, on what was to have been his last mission, and he spent 10 months

as a prisoner of war.

He became an ace (a pilot shooting down at least five enemy planes) in the

Korean War as well, flying an F- 86 Sabre jet. He shot down six Soviet-

built MIG-15 fighters and shared credit for the downing of another.

Almost three decades later, Mr. Gabreski faced a challenge he could not

surmount when he tried to run the troubled Long Island Rail Road, the

nation's busiest commuter line. He became its president in August 1978,

months after a cold wave battered the railroad. He resigned under pressure

in February 1981, months after a heat wave battered it anew.

By the end of World War II, only three American pilots - Maj. Richard Bong

with 40 "kills," Maj. Thomas McGuire with 38 and Cmdr. David McCampbell of

the Navy with 34, all in the Pacific theater - had eclipsed Mr. Gabreski's

total.

"Wait till you get 'em right in the sights," he once said, explaining his

technique. "Then short bursts. There's no use melting your guns."

Francis Stanley Gabreski was born in Oil City, Pa., on Jan. 28, 1919, one

of five children of Polish immigrants. When he was 13, his father, a

grocer, took him to Cleveland to see an air race, and he found a lifelong

hero: the race's winner, Jimmy Doolittle, who would command the Eighth Air

Force in World War II.

Following the path of an older brother, Mr. Gabreski attended Notre Dame,

but he was captivated by flying lessons and left college in the summer of

1940, after his sophomore year, to join an Army Air Corps cadet program.

He completed the cadet program, graduated from basic training in March

1941 as a second lieutenant, and joined a fighter unit at Wheeler Field in

Hawaii. On the morning of Dec. 7, 1941, he was shaving when he heard the

roar of low-flying aircraft and the rumble of explosions. He scrambled to

a P-36 fighter and flew over Pearl Harbor at 4,000 feet. American ships

lay on their sides, burning, but the Japanese aircraft were nowhere in

sight.

But because he spoke Polish and "I felt strongly about what the Nazis had

done to Poland," he asked to be assigned to a Polish fighter unit attached

to the Royal Air Force. He flew some two dozen missions over Europe with

Polish pilots early in 1943 before joining the United States 56th Fighter

Group in Britain.

On Aug. 24, 1943, he was escorting American bombers, flying at 27,000 feet

near ÀEvreux, France, when he spotted seven Focke-Wulf 190's flying 10,000

feet below. He put his plane into a dive, got behind the flight leader,

shot up the fuselage and wings, and saw the plane plummet.

He had his first kill.

His best day was May 22, 1944, when he shot down three Focke- Wulfs near

Bremen, Germany. On July 5, flying near ÀEvreux, he downed his 28th German

plane, becoming the No. 1 American air ace of the war at that point.

He was a celebrity, and the War Department wanted him home to help sell

war bonds. So he wrote to his fiancÀee asking that wedding plans go into

full swing. His hometown, Oil City, raised $2,000 as a wedding gift and

planned a parade.

He was to depart from the air base at

Boxted, England, on July 20 for 30 days' leave. But at the last moment, he

asked to go along on a mission to escort B-24 Liberator bombers that would

attack railroad yards near Frankfurt, Germany.

After the bombers completed their run, he strafed an airfield seven

miles west of Koblenz, but he came in too low, causing his propeller to

hit the ground, which made the engine vibrate. He crash-landed in a wheat

field, and after spending five days moving through the countryside, he was

picked up by a farmer and turned over to German authorities.

An interrogator told him, "We have been expecting you for a long

time," and showed him a file that held a copy of the military newspaper

Stars and Stripes describing his milestone 28th kill.

He was taken to a large prisoner of war camp on the Baltic Sea and

remained there until Germany surrendered in May 1945.

When he returned home, he went ahead with the interrupted wedding and

married Catherine Cochran, known as Kay, on June 11, 1945. She died in a

car accident in 1993.

Mr. Gabreski is survived by three sons, Donald, of Dayton, Ohio;

Robert, of Holmes Beach, Fla., and James, of Melbourne, Fla; six

daughters, Djoni Murphy of Trego, Wis.; Mary Ann Bruno of Dana Point,

Calif.; Frances Phillips of Westhampton Beach, N.Y.; Patricia Covino of

Quogue, N.Y.; Linda Kay Gabreski of Huntington Station, N.Y.; and Debbie

Ann Burkhardt of South Huntington, N.Y.; two sisters, Bernice Stanczak of

New Castle, Pa., and Lottie Kocan of Erie, Pa.; 18 grandchildren and 4

great-grandchildren.

Mr. Gabreski worked briefly for Douglas Aircraft after the war, then

rejoined the military and returned to action in the Korean War. He served

as commander of the 51st Fighter Wing and returned to the United States in

June 1952. He received a ticker-tape parade in San Francisco and was

greeted by President Truman at the White House.

He retired from the Air Force as a colonel in 1967 after having served

for three years as commander of the 52d Fighter Interceptor Wing at

Suffolk County Air Force Base in Westhampton Beach. The field, now a

general-aviation airport owned by the county and used as well by the New

York Air National Guard 106th Rescue Group, was subsequently renamed

Francis S. Gabreski Airport.

Mr. Gabreski held executive positions with Grumman Aerospace until

August 1978, when he was named president of the Long Island Rail Road at

Gov. Hugh L. Carey's behest.

He would remember telling a Grumman colleague at the time how he

"didn't know anything about Lionel toy trains, let alone a real commuter

line." But his Polish background and his identification with Long Island

were attractive political attributes for Governor Carey, who was facing a

Democratic primary challenge from Lt. Gov. Mary Anne Krupsak, who was of

Polish extraction. Moreover, the Republican gubernatorial candidate,

Assembly Minority Leader Perry B. Duryea, was from Montauk and had charged

that Mr. Carey was inattentive to Long Island's needs.

Mr. Gabreski sought out commuters, seeking to win good will for the

line, which had long been plagued by malfunctioning equipment. But he was

unable to turn things around and was unfortunate enough to encounter a

heat wave in 1980 that proved too much for the railroad's air-conditioning

systems.

Something he had enjoyed through all his missions in Europe and Korea

had deserted him. "A pilot can contribute physical acumen, good eyesight

and alertness," he once said. "You have to be calm, cool and collected.

Freeze, and you frighten yourself."

"But," he added, "beyond that you need some luck to survive."